Reading Room

A look at my library. Twenty years in NYC. Notes on February, books, and home.

February is the shortest month with the longest memory. It’s a time we love to hate. It’s also a time when we think about time because it’s too cold to do anything else.

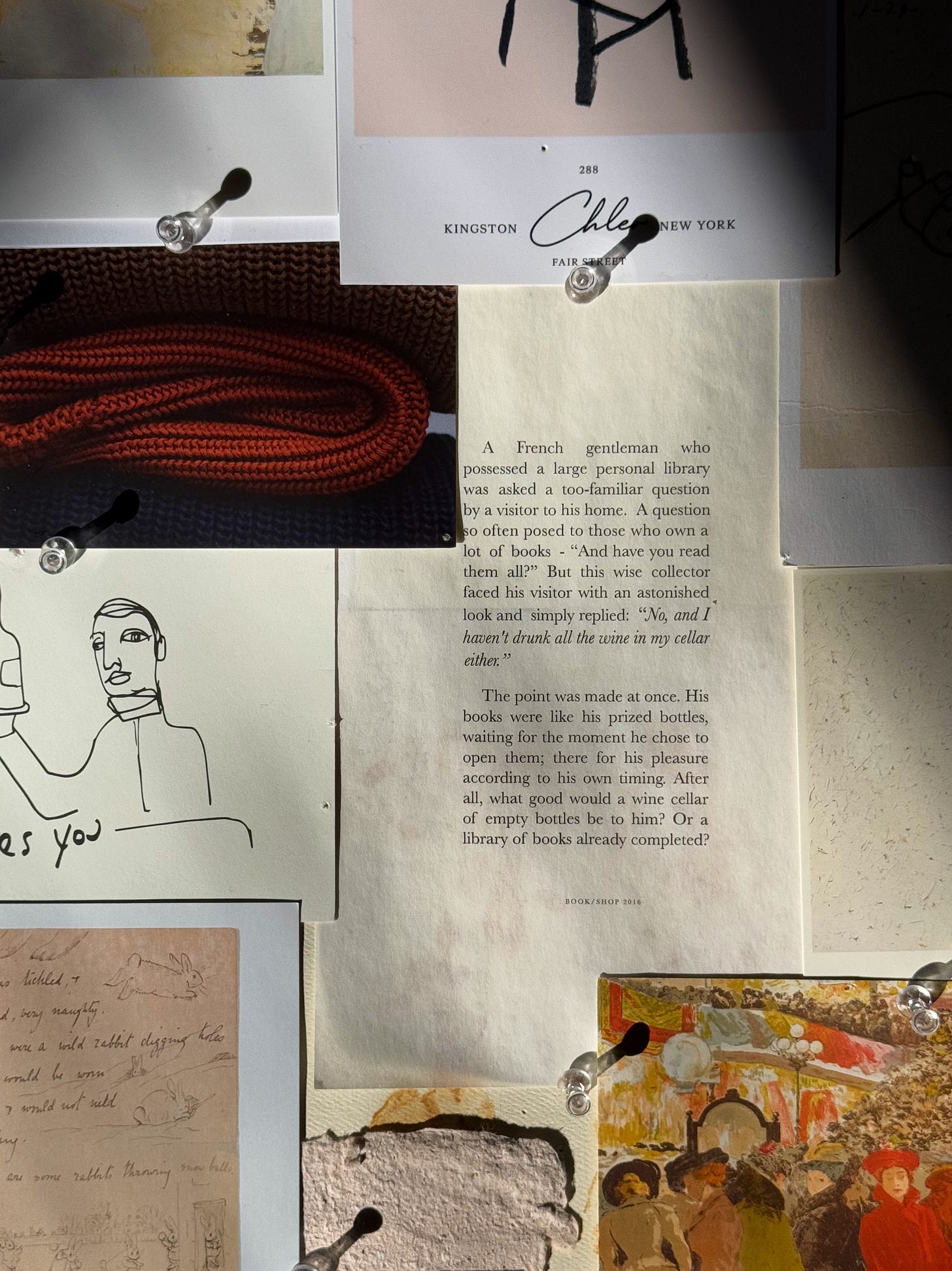

Last February, my husband John and I stood in the middle of Paula Cooper Gallery on the final day of the group exhibition, “Books.” I was drawn to the show's premise, a “[demonstration of] the many ways in which contemporary artists have engaged with the book as surface, structure, found object, and philosophical guide.”

There is a difference between looking at books and reading them, but each act offers unique pleasures. From the gallery’s website: “Reading, collecting, and fabricating books informs a particular way of creative thinking, in which a double-page spread, a fabric-bound volume, or an illustrious typeface become crucial components of works of art. … There will be books on shelves, indicating how intensely revelatory a library can be about its owner, and sculptures incorporating books as found objects will embrace the book as a talisman, gesturing to the acute historical specificity of a volume that originated in a particular place and time.”

I was struck by the phrasing—how intensely revelatory a library can be about its owner—as if the books are creating the person and not the other way around.

Books have always been a big part of my life, but I can identify the difference between who I was before I started reading (again, in adulthood) and who I was after.

My previous creative pursuits were story-centric and filled with beauty and opportunity. They helped me cultivate my taste and aesthetic interests. I was never more attuned to my body (for better and for worse) than mid-pirouette or trying on a well-tailored coat. But for a long time, I couldn’t go as deeply as I wanted. While those endeavors got me into the world and out of my head, I forgot how to come home to myself.

I’ve carried some qualities from these past chapters into my current reading/writing life—particularly when it comes to body language and the senses: sighing from the day’s disappointments or delights before pulling a book off the shelf, smiling at the first page as if it’s going to return the gesture.

There is a physicality to reading, a subtle exchange. In The Beauty of Light, Etel Adnan remarks to Laure Adler about talking to flowers (and giving them agency to speak back). In Shifting the Silence, she suggests that other humans aren’t the only beings that can be one’s friends.

For many, books are friends with distinct voices and demeanors. They slouch over—pages to the floor, spine to the sky. Other times, they stand tall, sandwiched between forests of potted plants and flickering candles. They aren’t sentient but can instill a level of consciousness. Pick up a book and pick up a life. As Kimberly King Parsons, author of We Were the Universe and Black Light, shared: “Reading is a meditative, relaxing act that slows me down, but sometimes I find scanning [or] touching the spines of my books to be blissfully invigorating too, almost like I can hear little snippets of voice from each author as I touch them.”

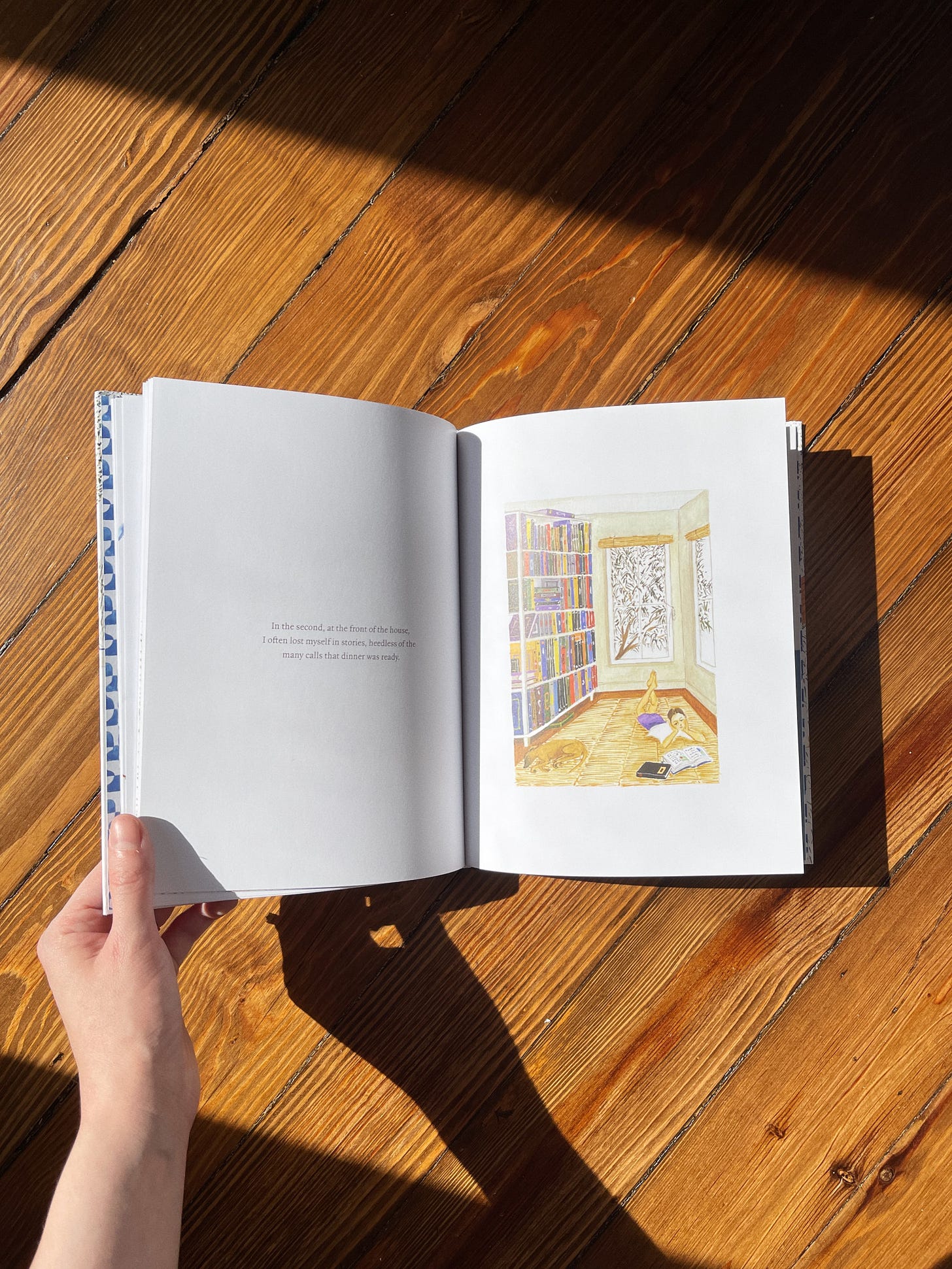

In the presence of books, we aren’t as alone as we might think—a chorus of voices rushes to fill our hearts and homes. To that end, I like how Alina Grabowski, author of Women and Children First, described the singular joy of reading at home: “I love to lie, I love to flop, I love to lounge. If I'm reading in public, I still feel a need to be respectable. I can't flick my shoes off, take up an entire couch, or just generally forget about the amount of space I'm occupying and how I'm occupying it. There's this pleasurable lack of self-awareness that comes with reading at home. Plus, I can have one of our cats on my lap.”

This February, a sleek black cat circled my feet as John and I perused the shelves inside High Valley Books, a parlor and basement-level bookstore run by Bill Hall out of his house in Greenpoint. Sounds of rustling papers and soft chatter drifted throughout the halls. It was clear that everyone here held storytelling in high regard.

Usually, I would have spent several hours surveying Hall’s incredible collection, but in the presence of someone else’s home—glimpsing mail in the vestibule, a stray coat draped on the banister—I suddenly wanted nothing more than to return to mine. I left empty-handed, burning with a desire for something I couldn’t quite name: Something between reading and living.

In recent weeks, I’ve been stalled by other modes of being: Maybe wintering or languishing. For some reason, the word visiting comes to mind, too.

···

Twenty years ago, my family and I moved to New York City on an ordinary February night. We’d never visited, but I immediately felt at home with its rhythms. As I write in my book, Slowing:

“When we finally arrived in New York many months later, it was dark: the hollow stretch between midnight and morning that feels like forever if you’re a kid biding your time. An ink blanket covered the winter sky; a few specks of light cut through its earthen seams. We turned the corner onto Queens Boulevard. I yawned sleepily, my mouth agape and ready to absorb the color and light swiveling out in all directions. … Here we were, about to settle into new rhythms in yet another new place. Only now, the sky glittered with possibility.”

Possibility swelled across the boroughs, where I engaged with art, dance, music, nature, and fashion. Books remained a part of my days—keeping me and my best friend company while we hung out amid the YA shelves at Barnes & Noble, perusing fashion history books at Strand—but more than anything, I was learning to read the room.

I noticed a pattern developing after finding myself in various creative environments: As a dance student, I relished attending ballet classes to observe the sensorial chaos and people-watch at the communal barre. Later, I spent years visiting artists and makers at their studios, falling in love with their processes even more than their products. Often, these studios doubled as their home, and the dissolving boundary between personal and creative space resonated with me deeply. I had grown up visiting my grandmother at her home studio outside of Albuquerque (a one-room barn she eventually moved into before leaving New Mexico entirely). I’d also always done my best work at home, transforming my many childhood bedrooms into imaginative spaces from floor to ceiling. Everything was a canvas.

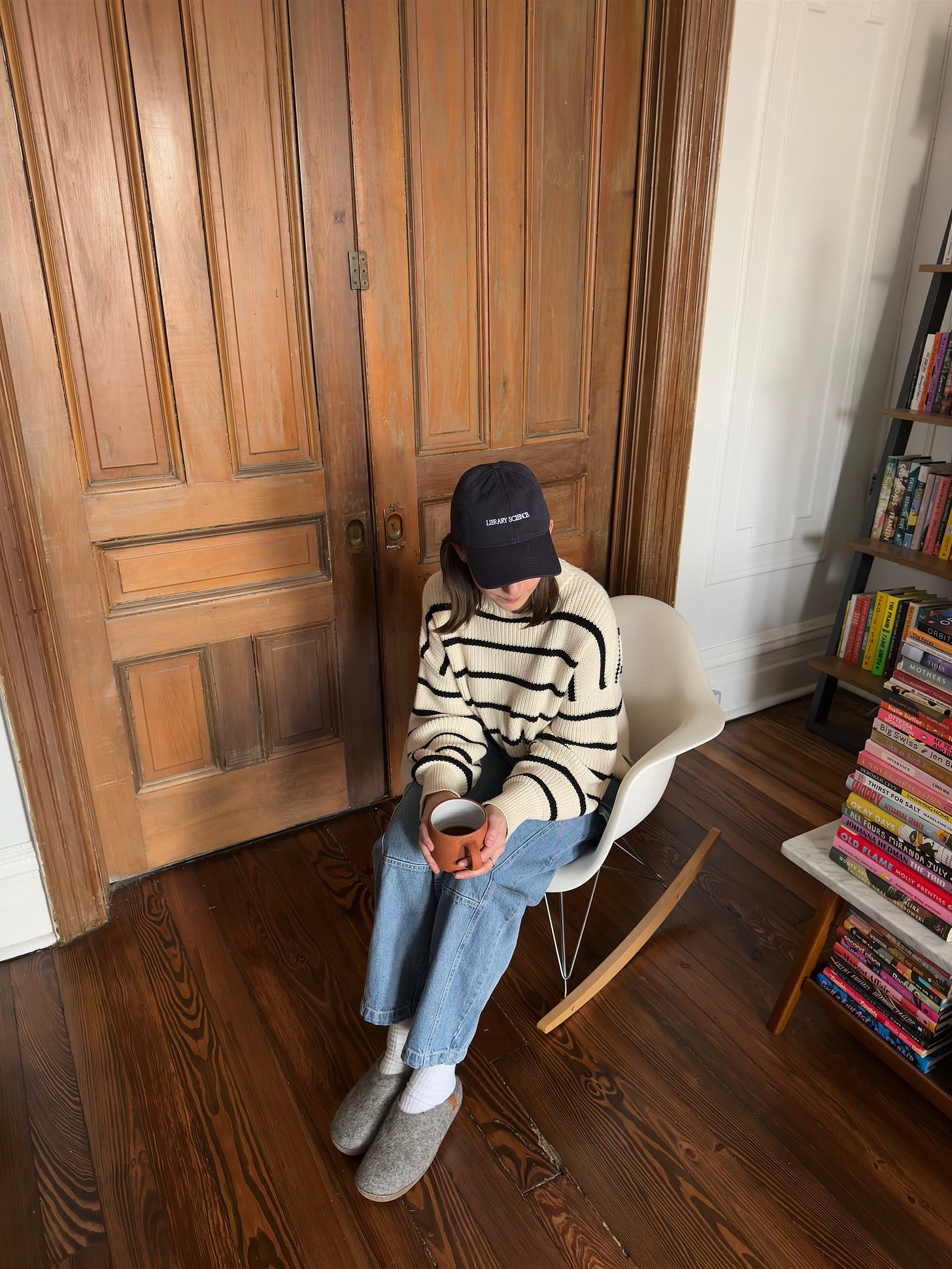

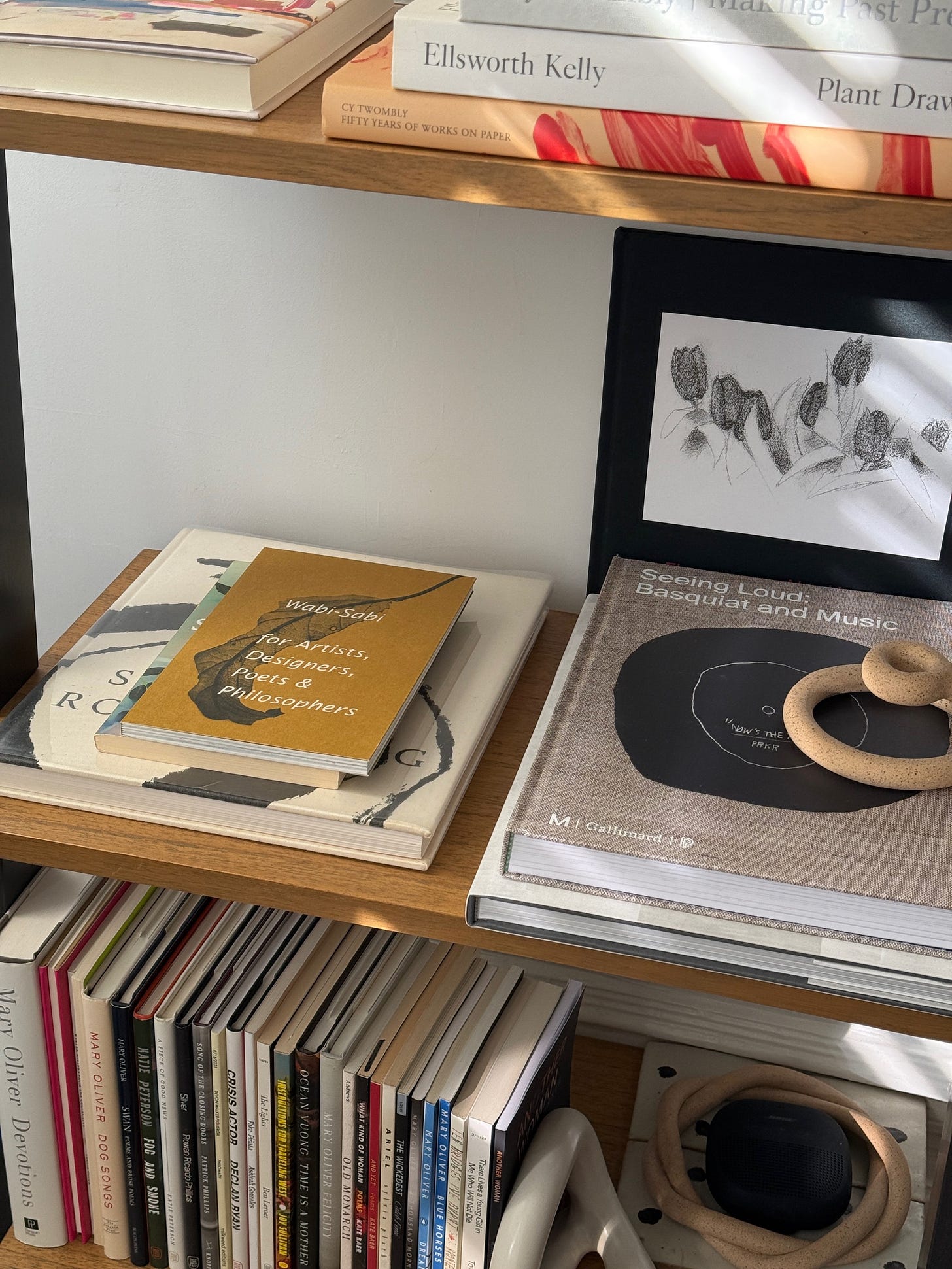

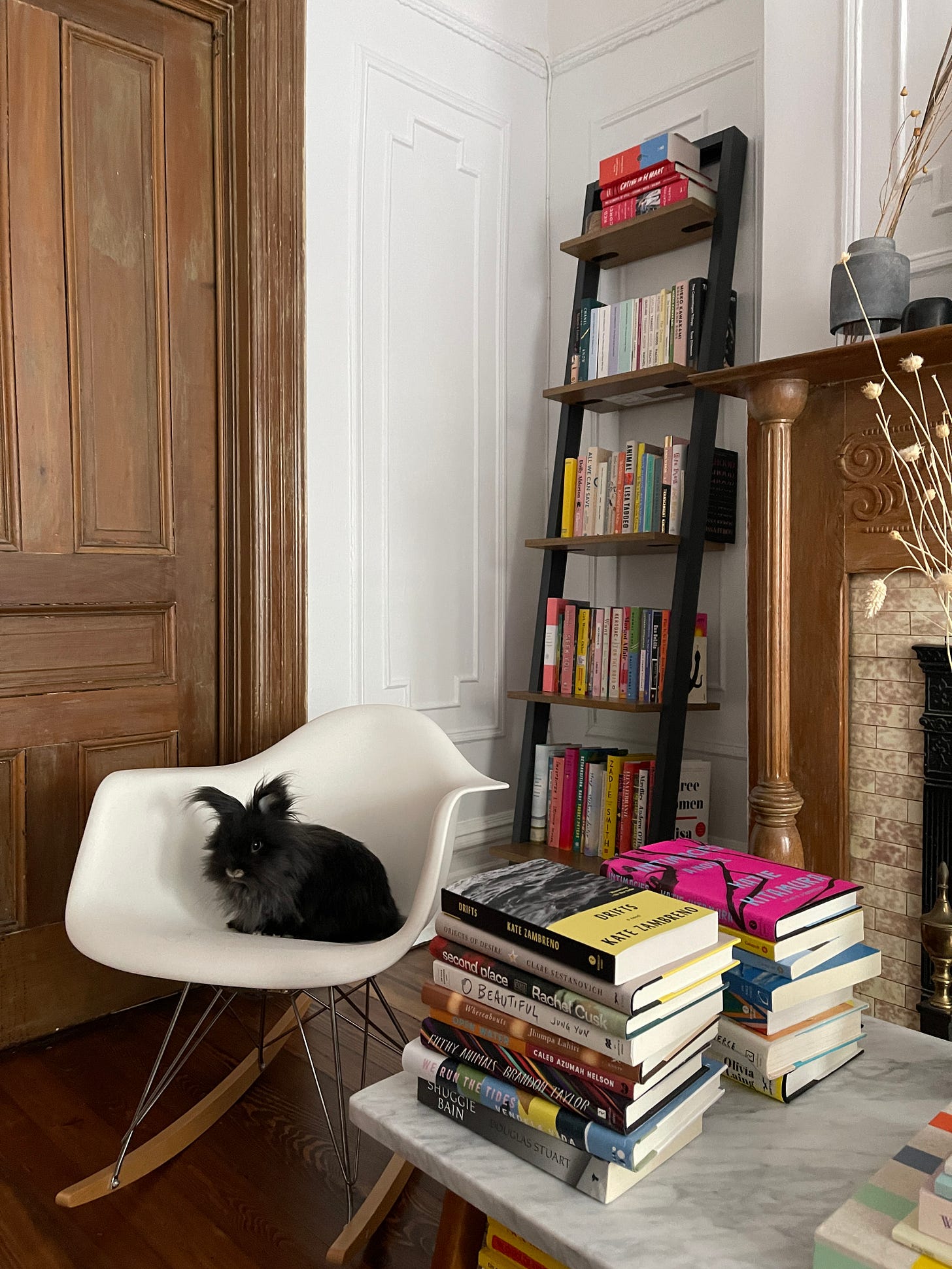

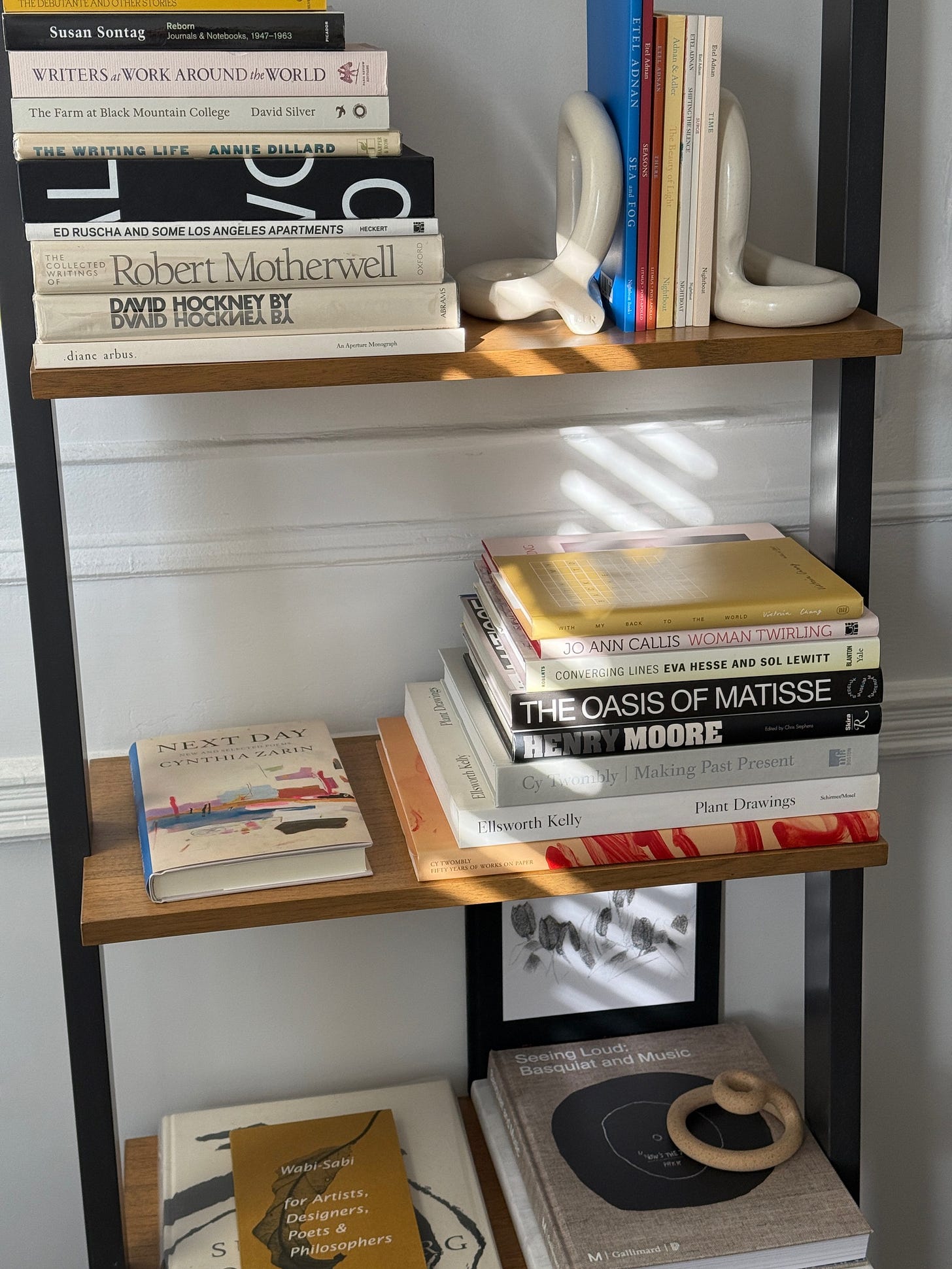

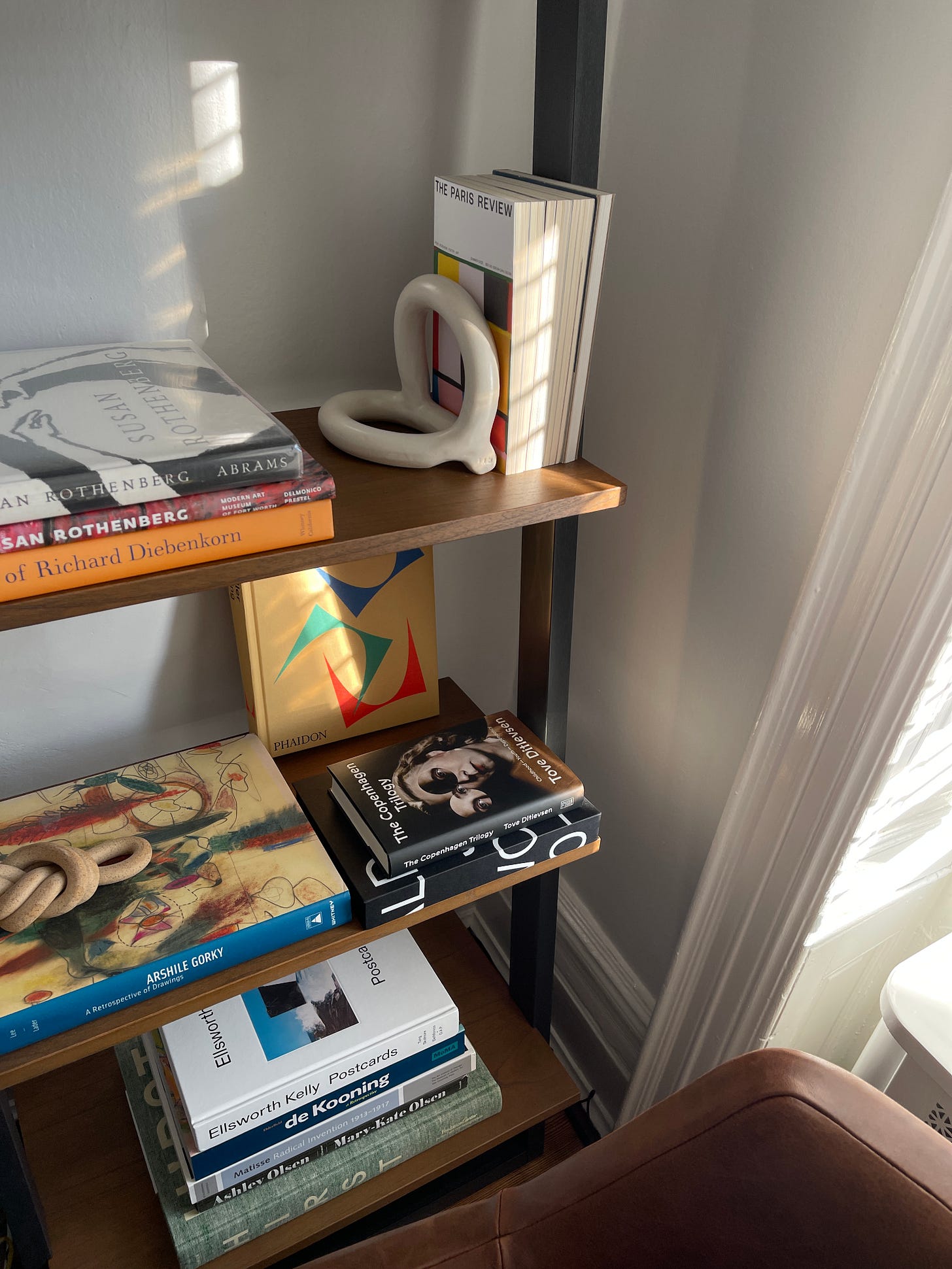

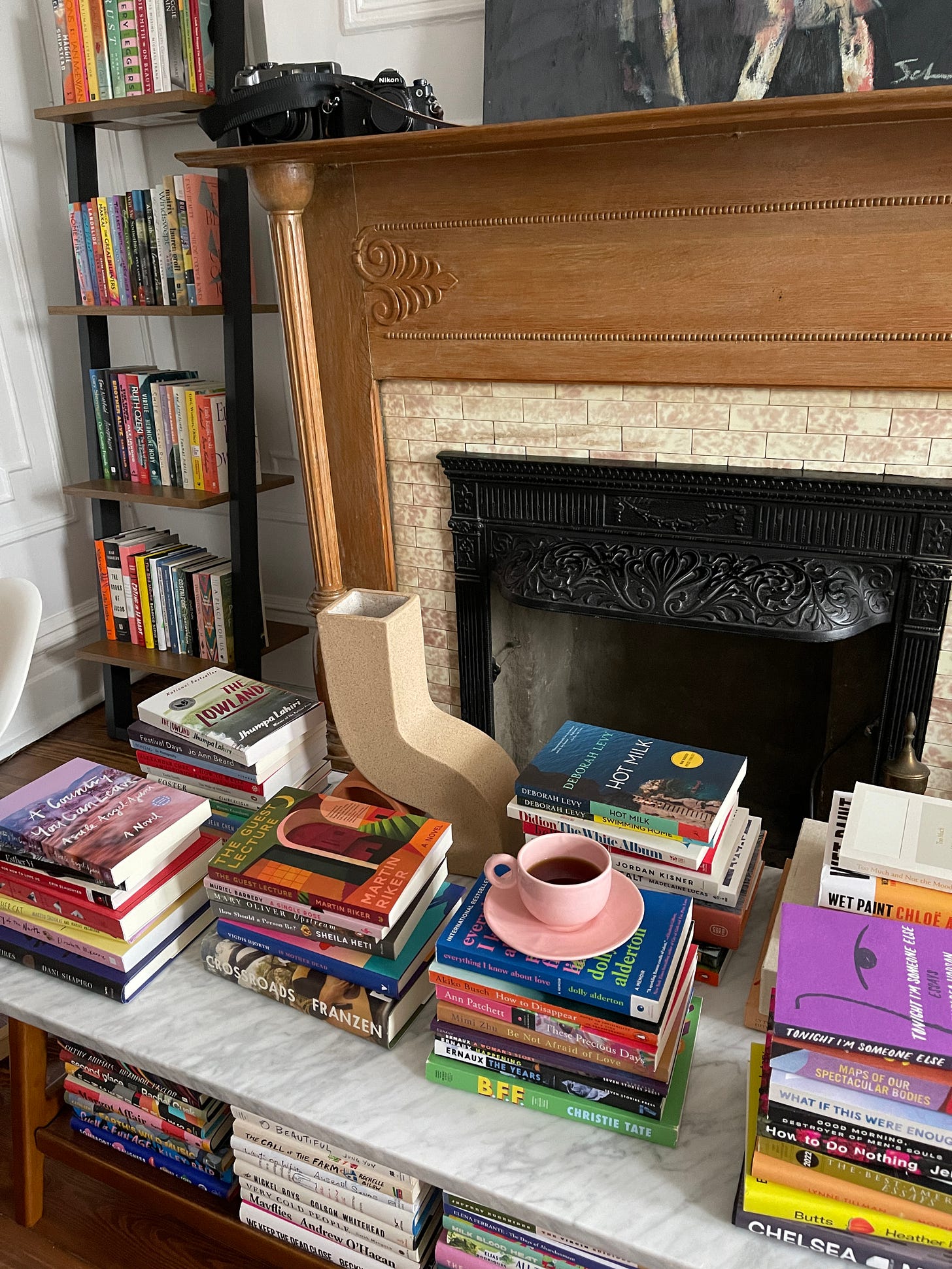

The same can be said for my current apartment. Design objects and artwork adorn each corner, but in this chapter of my story, you will find a book on nearly every available surface. As writer Ayşegül Savaş told me during our conversation for Slow Stories’ podcast: “ … being with my books gives me such a sense of security and comfort.”

In our dining room: shelves of poetry and art publications—because it seems appropriate to have such beauty within reach of our morning coffee. In our bedroom: novels and short stories that remind us how fiction helps us deal with the facts of life. In our home office (which we think was meant to be used as a nursery—an apt parallel for creation), essay collections, memoirs, and craft lectures that make me a little braver each time I sit down to write again.

Stand in the office doorway, and you can see our entire bedroom. Track the room from that vantage point from right to left: two windows facing a tree-lined street, a large mirror, our bed and dresser, a nonworking fireplace, a design-forward rocking chair sitting next to a marble coffee table that’s bending under the weight of many TBR towers. Technically, this was meant to be a living room, though I’ve referred to it as my reading room.

Gliding through the entire apartment, I realize how intimately I know it now—and at the same time, how little inside has changed, save for the steady accumulation of texts. “These simple transitions, such as walking through a trellis, or sitting down for breakfast, change your whole mood,” Elisa Gabbert writes her essay “Infinite Abundance on a Narrow Ledge” from Any Person Is the Only Self. “A room is a mood, and we need different moods, small and capacious. The past is more past when it happened somewhere else, with other qualities of light. The changes are needed—they make time more felt.”

After residing in over a dozen addresses across three states, it’s become a point of pride to tell people that I've lived in this apartment longer than anywhere else. Not to mention that finding it—in February, no less—felt like fate.

John’s parents were hanging out at our studio when he stumbled upon the open house. The apartment was right down the street from where we lived at the time (its address included the same numbers as our now-former studio but in a different order). They went to see it for fun, and though I was out of town, I agreed to sign the lease sight unseen after hearing the enthusiasm in John’s voice.

The photos didn’t do it justice. Rivulets of light spilled in from the windows, and historic moldings announced themselves in nearly every room. I’d never had so much space to play with when furnishing a home, but even with many knickknacks, something was missing—and that void went beyond interiors.

One day, I wandered into the tiny bookstore around the corner and found myself drawn to Elena Ferrante’s Neapolitan Novels. The following year, I picked up a literary journal—and then another. The year after that, in the depths of the pandemic, I devoured new releases under a patch of warm light in our bedroom—ultimately launching myself back onto the page as a writer. Slowly, I began to feel at home not only in aesthetic matters but heart and soul.

In the same essay, Gabbert references The Poetics of Space, where “Gaston Bachelard thinks a lot about [Rainer Maria] Rilke.”

“He notes Rilke’s obsession with furniture and things—so often, but not always, Things—the significance of insignificant objects. ‘For the sake of a single poem,’ Malte writes, ‘you must see many cities, many people and Things.’ ‘Familiar, intimate Things.’ ‘Things vibrate into one another… Every flower is everywhere.’ These life objects, the objects of our lives, have mythical, mystical significance. They contain life. They are ‘filled with significance, through and through.’

I think about the literary objects I initially brought into the space: popular debuts of the era (and some of my longtime favorites), like Emma Cline’s The Girls and Stephanie Danler’s Sweetbitter, various fashion and coffee table books, a few memoirs and business manifestos from digitally savvy entrepreneurs. Here was the foundation of my personal library—“filled with significance, through and through”—but one made for me by external influence.

Now, the apartment was asking me to make it my own.

In this way, the space has been a challenge, an oasis, and a constant when so much in our world has gone off the rails. Despite the chaos, reading here continues to be a singular experience: natural light dances across pages, my lionhead rabbit Pepper nibbles on a weathered book jacket, leaving bits of hay in the crease, floorboards emit a familiar whine as I sort through the (ever-growing) stack beside my bed. My library has expanded in directions I didn’t expect—and so has my life. In this home, I’ve become a reader again.

···

I don’t think it’s a coincidence that reading room sounds like breathing room. We need room to read—to breathe. To catch our breath. To confront things.

Above our bed, a large painting by my grandmother stands guard. Rendered in dark tones, the work depicts arrows in mid-air, but it doesn’t feel dangerous—rather like a calling. They point toward the towers and my favorite books, perhaps symbolizing power, strength, and all that can be endured. Something will have to give eventually. The shelves can’t bear the weight of it all forever, and neither can I.

In Savaş’s latest novel, The Anthropologists, a young couple searches for a (more permanent) home. “We had a routine; we grew fond of it,” the narrator tells us. “Perhaps we were tired of that first rush of excitement in a new setting, and the gradual draining away of color. Now it was time to expand. To make a life, as some people called it. We wouldn’t have called it that, but we agreed that we had to make things a bit more solid.”

John and I aren’t young anymore, at least by societal standards, yet it feels that way as we navigate home as a place, an expectation, and a narrative that’s ours to (re)define.

Maybe this is saying the hard part out loud, but I’ve always felt the most at home with (the idea of) adolescence. Launching myself into adulthood in New York happened fairly quickly, and I soon bought into the idea that a successful career could save me. (It did in some ways.) But in the following years, I quietly daydreamed about the glow of youth rather than the blue light of ambition: a crush spraypainting my name at 5 Pointz, hanging out at the Citibank building’s food court after school, attending a Fashion’s Night Out event or a reading at McNally Jackson followed by dinner at Cafe Gitane or Cafe Orlin, long talks about everything and nothing on delayed subway cars or apartment stoops.

As Tove Ditlevsen writes in the poem “My Best Time” from (the forthcoming) There Lives a Young Girl in Me Who Will Not Die:

The best time of my day

is when I am alone,

and my thoughts can grasp

a fleeting memory—

childhood’s half-light falls

through bare winter branches

landing in a stripe of sun

upon my writing desk.

I’m not sure if I would feel the same way had I not experienced this period in New York, but I have been revisiting it more often lately, and I’m grateful for it more than I can put into words. At the same time, twenty uninterrupted years in the city can alter your perception of time and place. Even though I’ve spent most of my time here as an adult, I have to remind myself that I was sixteen—sixteen years ago. Still, it will always be a city I associate with my youth: a chapter that began during the shortest month of the year but marked the longevity of my creative life.

Later in The Anthropologists, the couple reflects on an apartment they just toured. “We walked all the way back home, over an hour, crossing into the old city and out again, to shake off the visit. What was the lesson, then? And how were we meant to live?”

And: Where do we go from here?

A transient childhood instilled my reverence for home. A pandemic turned the concept on its head. In any case, I’ve wanted to hold onto it for as long as possible. That’s probably why it’s felt the most compelling for me to read—and be—in these kinds of spaces. Yet I’ve been thinking about what Rosalind Brown, author of Practice, shared with me: “I’m not a minimalist at all—I take a bourgeois pleasure in having possessions and being able to see them, so I like to have a bookshelf visibly crammed with books. But they can be distracting and anxious-making … Home isn’t always the most interesting reading environment in the long term. Some of my sharpest reading memories have been formed when I’ve been out reading a particular book in a particular place that I haven’t ever gone back to: Helen Garner’s Monkey Grip in a cafe in New York, for instance, or Gormenghast at a Tuscan villa aged sixteen. The place and the book intensify each other and remain undiluted.”

If a book is a portal, and “a room is a mood,” then perhaps a home is a promise. The promise of what you’ll find if you’re brave enough to leave it and the past—maybe not behind, but where you first found it: in your mind’s eye, in your heart. The kinds of places that are outside of time—ones you can always revisit.

Or rewrite.

As of this month, John and I have entered our seventh year in this apartment. I’ve told myself to start letting it go to advance the plot of our life. Because, sometimes, when I’m organizing the shelves—forcing a change in scenery when I can’t bring myself to leave—it feels like my books move more than I do. I know this isn’t true. I know they are emblems of experience and truth—possibility. I know I’ll winter, languish, and continue (re)visiting art in galleries, words on pages, and memories in motion. I know that I’ll cherish this place for as long as we’re lucky enough to call it home, which is in Brooklyn, which is in New York, which is in the United States, which is in the world. And the world is changing—for better and worse, at once, every single day. And as the days tumble into years that move me through spaces, stories, and February nights, I know I’m changing, too.

A LOOK AT MY LIBRARY

My library has changed a lot through the years. (You can follow me on Instagram for real-time updates on what I’m reading and recommending.)

PORTRAITS FROM THE PAST

Did anyone else obsessively document their life with a Fujifilm Instax camera? (Should I bring this back?) In honor of my twentieth anniversary in New York, here are a few snapshots that give you a nice visual of what I shared in this story.

Beautiful words

wow!! I am obsessed with how you have displayed your books - such a creative idea to make more space for books, I might have to try that!