The studio where I recorded Slowing’s forthcoming audiobook is situated inside a high-rise building I hadn’t realized I’d visited before until seeing it again from the street. My eyes traveled the distance from gummy concrete to storefronts filled with “I <3 NY” merchandise toward office windows all the way to the sign for the renowned dance apparel shop I frequented in my youth.

New York’s Theater District is home to cultural landmarks like Rockefeller Center and Radio City Music Hall. When I thought I would become a dancer, it was my home in many ways, too. Countless hours were spent between 42nd and 72nd Street taking classes, going to shows, occasionally performing myself, and constantly dreaming. Then, on a hot August day many years later, I stood at the center of a memory being remade in real time. The convergence of the past and present always happens in the city, but I hadn’t felt it so acutely in a while.

···

I’ve often said I wear my heart on my sleeve and my anxiety on my face. This was especially pertinent as I got adjusted to the cadences of reading—performing—my words.

The method was called punch and roll, which meant that if I messed up a line B—the sound engineer and a new pal—would play the recording until the error, and I would jump back in to redo the line. With an acting and performing background of his own, B relayed tips and tricks when it started to feel difficult to annunciate or overcome stubborn tongue twisters. Despite the expected flubs, we quickly learned that I was good at jumping back in—a little too good. Sometimes, I beat him to the punch.

I’d laugh to myself, knowing how much I’d jumped headfirst into things over the years, even if I didn’t always know my own motivations—and shortcomings. In fact, I tell a story in Slowing about diving in and overestimating my abilities in a ballet class. What I didn’t mention in the book was how, after exiting the building and finding myself back on the street in tears of exhaustion and humiliation, I had never felt more sure that the city would give me everything I needed to feel at my most creative—human.

It almost feels too easy to make the connection between New York, creativity, and time. To feed the longstanding narrative that this place runs on hustle and speed. It does—and it doesn’t. It’s also a city of slow burn, old and big enough to hold millions of people and the (years of) effort they carry with them.

···

Days into recording, B and I developed a rapport—a sense of trust that would create space for the vulnerability required to speak with equal conviction and levity. It was in that space our respective New York stories arose: how we at once revered and reviled it and questioned its role in our lives and livelihoods.

Heidi Julavits’ diary, The Folded Clock, had been my companion on the train rides to and from the studio. The book sat in my bag next to us, and as we chatted, a moment from one of her entries resurfaced in my mind:

“I am the one being sucked empty in New York; I am harried, I grow thin, I develop face rashes. I persist in staying there for nostalgic reasons; I always dreamed of living in New York, and I am intent on realizing (and realizing and realizing, to the point of total body dissolution) this dream. At a certain point, you ask yourself, ‘Is this where I am going to die?’ and the answer is yes. You have, without realizing it, committed your body to a plot.”

Plot of land or plot in a story?

Maybe both.

Though it was something I loved, I didn’t often connect dancing with plot. Telling a story was the last thing on my mind. I was intent on mastering and completing the movements, building muscle memory, and indulging in the lifestyle, which ultimately set me up to embrace the same patterns in early adulthood. I worked hard—and at the time, little else mattered. I was in New York, and if I wasn’t making sense or progress, at least I was making it here.

I’m often interested in art that comments on the tension between the body and mind, perhaps because it feels so embodied in the city. As I wrote in Slowing, this duality becomes pervasive, sometimes slowing me down in unwelcome ways. The same concerns emerged each time I entered the recording booth: While I felt ready to jump into the process, I also felt the frogs in my throat, clammy hands, and words dropping off. And the internal hiccups: Had I really written this? What had changed since then? If I felt differently now, would I be able to say it again in this way? On the other side of the wall, B’s gentle reminders rang true: I could wait a beat even after the pre-roll finished playing. The silences could stretch. I was center stage, but there was time—even when the city made it seem like there was anything but.

I took a few deep breaths (“box breathing” at B’s recommendation) before the last leg of the session. It reminded me of that transition in a ballet class when you move away from barre work to center combinations. B and I continued to chat about various things. Books—mine and others—naturally entered the conversation; Miranda July’s sophomore novel, All Fours, was among them. We gushed over her prose, and B mentioned he was on “the edge of his seat” while reading. That seemed like a good way to describe the experience.

All Fours follows a semi-famous artist who plans to drive cross-country from LA to NYC. Thirty minutes into her trip (after leaving her husband and child), she abruptly exits the freeway, holes up at a motel called the Excelsior—her room there becomes a place of reckoning, reflection, and transformation—and begins a different kind of journey.

Transitions and timelines are prominent themes in Slowing. Back in the booth, I couldn’t help but draw parallels between finding myself in a similar “room,” reflecting on the transition from child to adolescent to woman, from dancer to blogger to founder to writer, from moving fast to embracing slow to reflecting on both. All of this contemplation had existed in the same place (New York) in the same person (myself). The city had taught me to hold so much. I was learning what to do when the load became too much to bear.

···

There is a moment in All Fours when the narrator decides to dance for a character named Davey (he also happens to be an aspiring dancer), whom she has become fixated on. July’s prose aptly depicts the physicality of art, selfhood, and desire. (I don’t want to spoil it, but I’ll just say that some of the scenes put you firmly back in your body!) When I interviewed July about All Fours earlier this year, I asked if she felt there was a difference between writing about the body versus speaking about it physically. She replied:

"Gosh, I guess it does because you're alone with your body. Your body is who you're with. I think often, when I'm with someone else, I don't exactly know how to stay in my body. I'm hovering in the air between us or something. It's one of those things where you can write something quite nice and then realize it’s not true. There's beauty with the body, but often, if you're going to write truthfully, it isn't beautiful in the way that has been described to us again and again. I tried to catch myself a lot of times and get out of these well-worn grooves. Even if all the words are new that I'm choosing, [I] could still end up somewhere well-trodden. I think some of that was just time—I had to outgrow certain conclusions. … I was writing into the story and had to live in my body. My first conclusion, or desire, wasn't ultimately my deepest desire or the thing I was most curious about. That took really sticking with myself."

Back at home, I thought about how, in many ways, the same can be said for me about slowness—writing about slowing down takes me deeper into the state, and speaking about it reminds me how much of a practice it truly is.

I’ve often been asked how one can engage in slow living in a place like New York. The answer changes every day. To be an artist in New York is taxing on the mind and body, but it offers something generative if one can learn to embrace the connections found in ordinariness—the dailiness and disappointments—because beyond the hustle and grind and glamour that exists, too. In fact, it’s everything.

Like July, I’ve had to outgrow certain conclusions about how to live, work, and create more (intentionally) here. Like July, that really took sticking with myself.

···

I didn’t initially think that I was going to write about recording Slowing’s audiobook. It’s a tiring, beautiful, and intimate process. It’s you and the words—and a voice in your ear guiding you along. There are the expected lessons, of course: drink a ton of water, be prepared to start and stop a lot, and experience every emotion.

I think there’s also a lesson here about listening in less tangible ways: knowing when to tune out the unwanted noise or negative impulses. Listening to the rhythms of your life and how they mesh with the realities of (where you’re) living. Rolling with the punches when those realities don’t resemble how you initially imagined them. Transforming nerves into nerve. Having the nerve to try anyway, in the face of a city that delights and drowns you—sometimes in the same breath. And with the latter in mind, taking a breath and really thinking about how it makes you feel.

At some point, I mentioned to B that I started Slow Stories as a podcast first to keep using my physical voice, even though I believe I’m saying things all of the time: in images, gestures, even silences. The same is true for the audiobook. I’m still not a fan of public speaking, but I wanted the opportunity to express the stories that I’ve held so close for so long. To use my voice—however shakily—in every sense of the word.

It’s always surprising to me when someone compliments my speaking voice (July herself praised it!), but I’ve finally started to associate it with my mind. When I put the headphones back on, read my words aloud (some of which I originally questioned), and listened back, I realized they weren’t half-bad. They were meant to be written at that moment and moved me in a way dance never could. Yet, without taking those steps in and out of the (ballet) studio toward a stage and then a new life altogether, I might not have learned the value of slowing down.

In the stillness of the recording booth, I was moved by where I’d arrived: at a state of mind-body connection, in a city I love differently now, under a small spotlight of blue LED casting a glow on something I can’t always see or say, only feel.

Pre-orders are essential for all authors, but especially first-time authors. They indicate widespread interest and help secure placement in bookstores and other retailers. I've reached a critical point in my life and work, so your support in this way would mean the world to me!

AMAZON · BARNES & NOBLE · BOOKSHOP

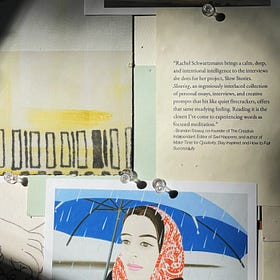

“In a day and age where ‘busy’ is a badge and productivity is paramount, Rachel Schwartzmann’s Slowing is an enchanting and soulful examination of what matters most: time, joy, creativity, and feelings. This is a beautiful book, filled with optimism and light.”

- Debbie Millman, author of Why Design Matters and host of the podcast Design Matters

Speaking of speaking out loud…

I’m thrilled to be launching Slowing at P&T Knitwear with the incredible Brandon Stosuy! RSVP here and learn more at the link below. (You can also revisit my podcast interview with Brandon and his collaborator Rose here.)

For Your Next Chapter

If you enjoyed this Slowing Process diary, check out the previous installments…

Styling SLOWING

Style and storytelling have always been anchors for me, both personally and professionally (I write about this in the book). As I prepare to bring Slowing into the world, the convergence of these two elements has been feeling more pronounced.

SLOWING: On Prompts

I didn’t initially set out to write a book that could be considered categorically self-help, but in addition to sharing my (slow) stories—and the stories of those I interviewed—I wanted to include an element that could help readers find or rewrite their own.

SLOWING: On Interviews

Questions and answers are the bedrock of our lives. We ask for information, meaning, connection. We respond with what we have available to us—whether it’s a long story or a small shrug. To me, the practice of interviewing embodies the adage it’s about the journey, not the destination. I walk away invigorated and sometimes exhausted from an interview, but always more human.

SLOWING: A Color Story

For the purposes of this design diary, I keep coming back to color. I wondered what palette would best convey Slowing’s pillars—time, pace, and creativity—without leaning too heavily into certain wellness trends.

Meet SLOWING

I knew it would be the thing I wrote before writing anything else. I'd been moving so much and so quickly for so long. I needed a place to set some of this down and untangle a lifetime’s worth of stories. And I did. But there was a lot I didn't know throughout this process, namely the nuances of publishing a book—a beautiful, chaotic, and singular experience. I learned that things can change when you least expect it, and as a result, you change, too.