From Cedars-Sinai: “The average person is born with 33 individual bones (the vertebrae) that interact and connect with each other through flexible joints called facets. By the time a person becomes an adult most have only 24 vertebrae because some vertebrae at the bottom end of the spine fuse together during normal growth and development.”

From yours truly: twenty-four reflections on bodies and bodies of work, on fear and creative courage.

There is the way you hold your book and the way your book holds you.

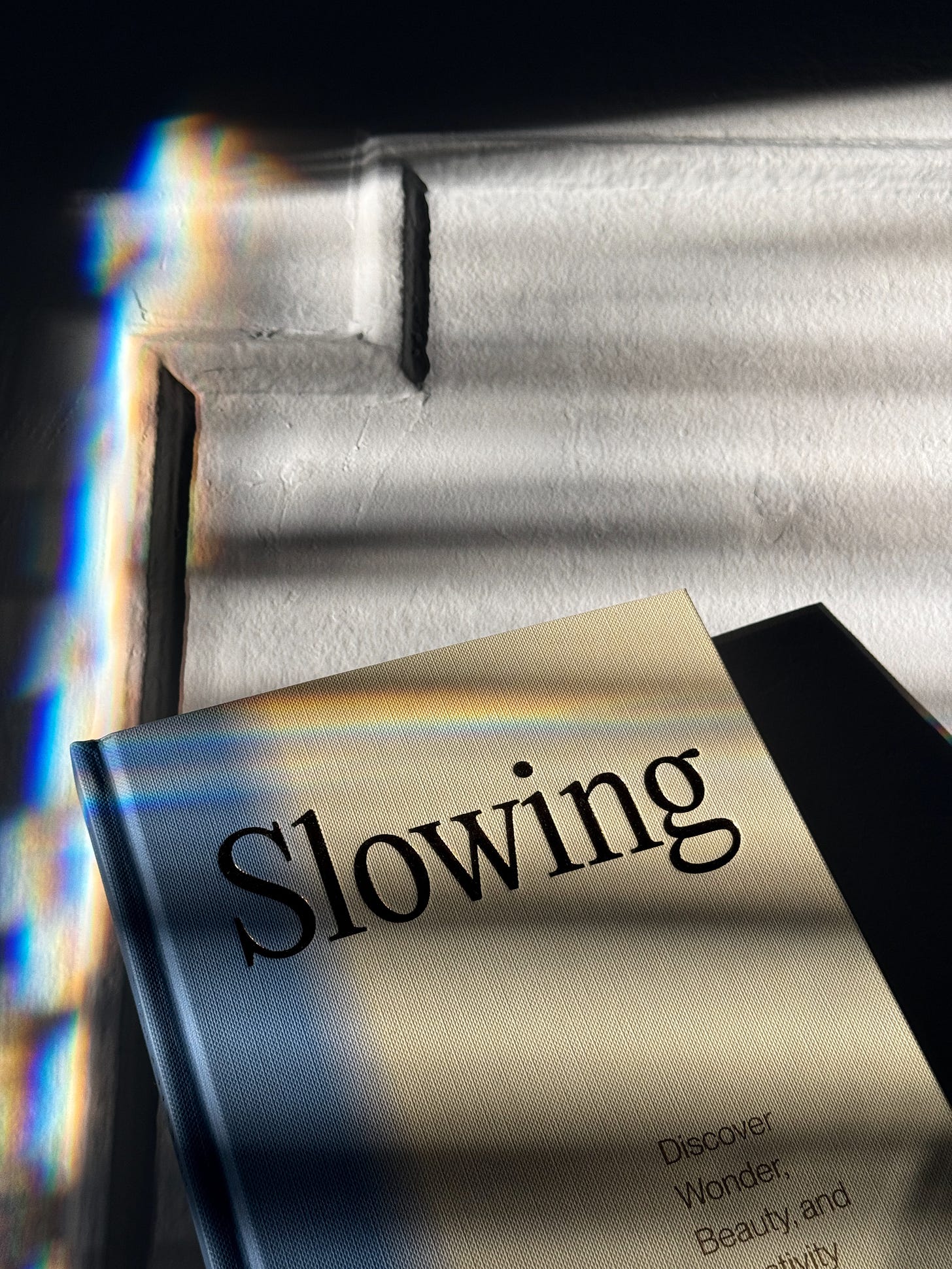

When Slowing is in my hands, I find myself stroking its spine, feeling the debossed title, watching the gold foil glisten in the light. There is so much inside its 6x8 paper body. According to Merriam-Webster, “Spine goes back to the 15th century, and it is derived from Latin spina, which can mean ‘thorn’ or ‘backbone’ (which are also two of the original meanings of spine in English). The word was first applied to the back of a book to which the pages are attached—or the part that shows as the book ordinarily stands on a shelf that is often lettered with the title and the author's and publisher's name—in the early 20th century.”

Earlier this month, I held Slowing toward my laptop screen as I spoke to a group of writers trying to finish their books. I was tired—but I didn’t tell them that. There were a lot of things I didn’t say, in fact, like how I wanted to slow down talking about slowing down. That I’ve also been reflecting on another growing creative preoccupation: the mind-body connection and its influence on art, anxiety, home, and family. This was especially pertinent when I felt a sharp shooting pain in my lower back, reminding me to get up and move away from my desk, where, after the event, I’d remained hunched over for a few hours working on various projects. I needed to stand up, stretch, and walk away from it all to move closer to myself.

Outside, a cool blast of crisp air; swaths of white web and foraged leaves artfully arranged on iron banisters and gates; furry spiders and homemade ghosts dangling from tree branches. Perhaps most interestingly, more skeletons than I’d seen in previous years. It seemed that every home called upon their presence. Some were small—doll-like—sitting in lawn chairs, wearing baseball caps and holding soda cans. Others loomed as large and tall as the buildings they guarded.

Every year, my neighborhood produces the most spectacular Halloween decorations. Families descend upon the streets for what my husband and I affectionately call the witching hour. Children’s howls of delight and surprise coat the air until dusk. It’s all fun and games—but this year, no doubt, feels different.

On the one hand, it’s a season of tangible transition: of leaves warming in color and temperatures (supposedly) cooling the air, of sweet candy and cheer, of publishing a book and realizing a dream. On the other hand, a potential unraveling of the collective.

Tricks and treats and complicated truths.

I’ve never been one for gory horror stories, but I do have a nuanced relationship with being scared—in life and creativity. The irony of writing about this as we face an uncertain future has me wondering about our capacity for fear—and how humans continue to be responsible for so much of it.

In this way, the decorative skeletons served as a mirror—an inquiry into what makes us who we are and what keeps us upright. As explained by the National Spine Health Foundation, “The spine does more than just hold us up. It’s also a highway for information. The nerves of the spinal cord are like a bundle of wires that carry messages between our brain and the rest of our body.”

On my way home, an unexpected laugh erupted from one of the Halloween-laden stoops. A cluster of skeletons remained still. Orange and black trimmings bristled in the wind. The soundtrack of spooky noises continued, though I could not locate the primary source of the sound—the feeling.

“If I didn’t have to speak all day, I wouldn’t,” I said to the group, half-joking. “Still, I never let that fear or discomfort stop me from trying to connect and make things.”

It isn’t always easy to reconcile my quietness and curiosity. But writing is in concert with feeling (fear included)—and (creative) courage is a feeling just as much as an action: It thrives in temperate conditions, unlike the hot lash of anxiety or the cold rush of terror. It requires the telling and—sometimes uncomfortable—appraisal of the self.

From Joan Didion’s “On Self-Respect:” “People who respect themselves are willing to accept the risk … They are willing to invest something of themselves; they may not play at all, but when they do play, they know the odds.”

What I didn’t say to the group: The odds of publishing are slim, and I overcame them. I also know how much is at stake beyond the page—mind, body, and soul.

Slowing has been in the world for over a month. I also know the world as we know it could change in the coming days. Again.

The skeletons will come down, and the costumes will come off, but what’s deep inside us will require nurturing—facing.

We are encouraged to meet the moment—to face our fears, to grow a spine. But throughout this process, I’ve learned creative courage is a part of our anatomy: We all carry it differently, just like stress and anxiety. We strengthen muscles. We build routines and practices. We tend to ailments. We manage expectations. We acknowledge our differences. We find a way to turn growing pains into pathways for growth.

When I stand up, I don’t always stand tall. My posture may say something to the world, but it doesn’t determine my strength.

“A healthy spine has three natural curves that make an S-shape. These curves work as shock absorbers to protect your spine from injury.” S is for slow, even if the process is not always steady.

Fear is a steady drip these days, but as it pools at my feet, my mired reflection within the chaos reminds me that I’ve—we’ve—made it this far. We’ve made art to try to understand the world and ourselves. We (can and should) keep going.

The moderator (a writer I admire deeply) said that I struck her as someone who, when presented with a challenge, “figures it out.” Slowing’s in-person event last week at P&T Knitwear confirmed that fact. Microphone in hand, it was gratifying—and necessary—to tell my story on the other side of this book, to recount my many creative chapters and the accumulation of experience and resilience that ultimately brought me to this point and, more importantly, back to myself. My fear didn't get the better of me. It was the first time—in a long time—that I felt at home in my body despite the amount of noise swirling in and around it. Somehow, I had been more articulate in a crowd rather than in the quiet of my apartment. Removing the screen, placing myself in the center of it all, allowed the fear to alchemize into something else, maybe even something generative. Communal.

So, what am I really saying here? It’s okay to be afraid, but don’t lose sight of your strength and courage, both on and off the page. Don’t lose sight of each other.

Slowing is one word, but it’s also the backbone of my and others’ slow stories. It’s a book, but it’s also a highway for information—and hope.

When I glimpse its beautiful blue spine, a chill runs down my own, reminding me of my nerves and nerve. Of bones growing, hearts beating, and minds expanding. Of thoughts coalescing into stories we’re trying to tell and the ones trying to tell us something back.

On the note of minds, bodies, and souls—and (creative) courage— please vote. 💙 Your voice matters.

For Your Next Chapter

If you enjoyed this Slowing diary, check out the previous installments…

"It’s okay to be afraid, but don’t lose sight of your strength and courage, both on and off the page. Don’t lose sight of each other."

Beautiful, Rachel 🖤

Thank you for your words. I appreciate you and your work. :)